How to Give Directions That Promote Cooperation

I was once was working with a high school student (for this purpose will go by the pseudonym Taylor) who was really struggling in some of his classes. High school is a whole new ball game for so many students because of the constant shift in environments, routines, staff, and demands. During the meeting with his school team a few staff noted that Taylor was “struggling with authority and following directions." However, one of his teachers noted he never had any issues with him. I met with Taylor in my office the next day and worked on building rapport. We discussed what was going on. He said that most of his teachers were "rude" and "mean" when they spoke to him, except for Teacher A (this was the teacher that said he never had any issues with Taylor).

As we know, behavior is influenced by the environment in which it occurs – which begged the question: What was different? What was so different between Teacher A's classroom and the rest of the periods? From Taylor's perspective, the way he perceived staff speaking to him was aversive, which likely had something to do with the constant escalations. Since staff behavior influences student behavior, and student behavior influences staff behavior, I was aware there was likely an underlying reason for staff speaking to him in a specific way. There could be a whole slew of things going on, so I scheduled a time to see things in action.

Taylor walked in calmly to first period with the rest of the students. He was timely and got right to his seat. Some students threw their hats on the table, but Taylor’s hood stayed on. His teacher smiled and started walking around the room. He then stopped at Taylor’s desk, crouched down beside him, whispered something, and gestured for him to push his hood back. His teacher got up and continued around the room. Without hesitation Taylor calmly pushed his hood back and looked at the teacher. His teacher glanced his way, winked, and gave him a thumbs up. I immediately had a hunch about one of the key differences between Teacher A's classroom and the other classrooms - how staff gave instructions to him...and upon observing his other classes, my hunch was correct. Now, there were some underlying issues going on that needed to be solved such as why Taylor kept his hood on in the first place, but for the purpose of this post I want to focus on one component of Taylor's environment that played a big role in how his day went, and this was how staff were speaking to him when giving a direction.

Giving a direction – such a simple thing us educators do all day long that most of likely don’t even think about the directions we are giving. We label these students who balk at directions as “oppositional” and “defiant,” but it’s imperative we stop to examine how we get to this place. It’s crucial that we examine how we are giving the demand. For some students, such as Taylor, we need to consider how to package up our directions in a way that will be better received. This is a case of “I need to fix what I’m doing” rather than “the student just needs to suck it up and comply.

Now, at first hearing there are a few things we should be doing before, during, and after giving a direction, you may be thinking, “I don’t have time to remember to do all of those things! I have a class to teach.” But when it comes down to it, all we are really doing is being nice. Speak to your students as you would want to be spoken to. You need to throw your “I’m in charge, they just need to listen no matter what” attitude out the door if you want positive behavior change – it’s many times as simple as that.

Here are some highly effective behaviors we ourselves should be engaging when giving a direction to a student like Taylor to increase the likelihood of cooperation:

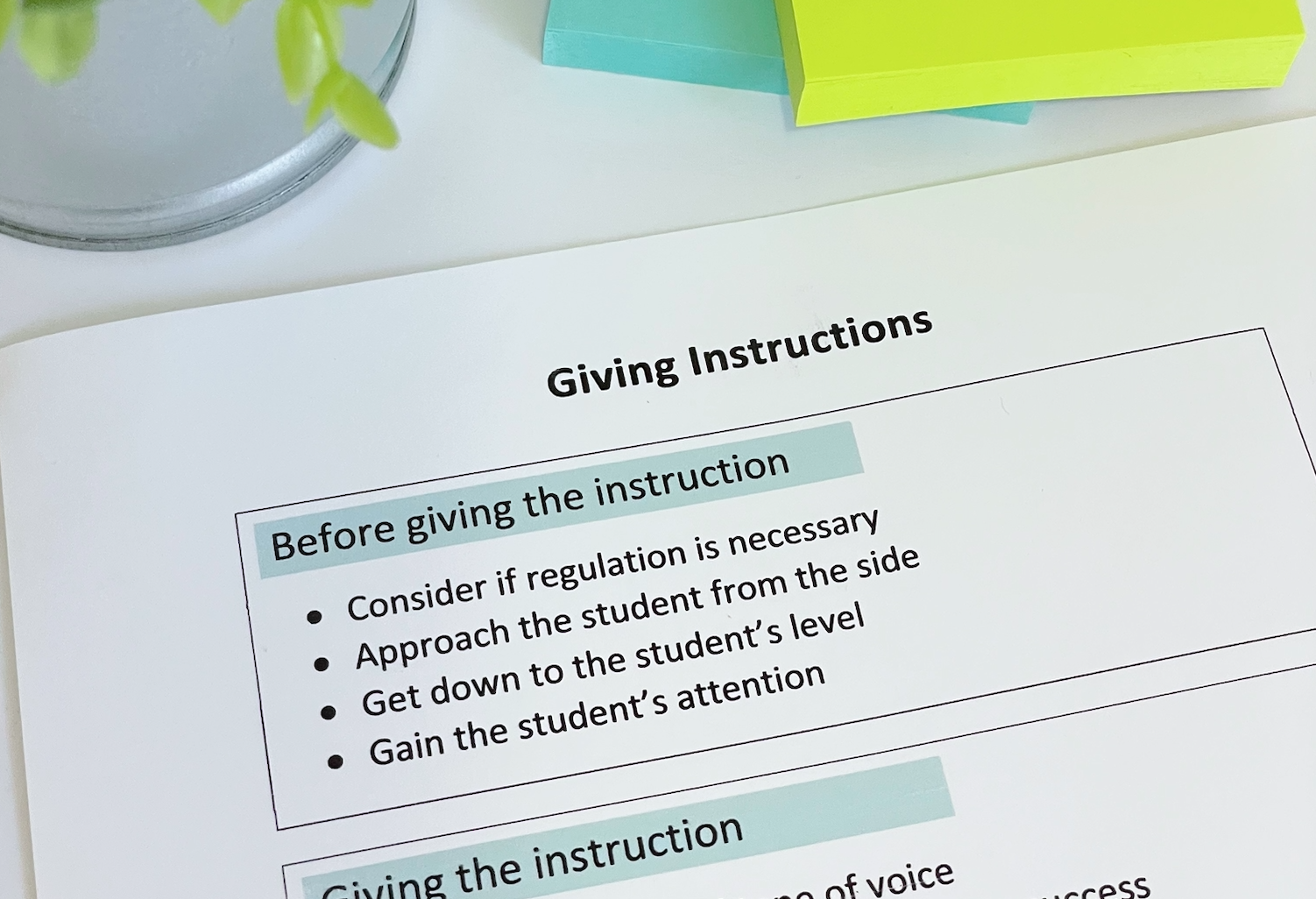

Before the direction:

- Consider if regulation is necessary

- Approach the student from the side

- Get down to the student’s level

- Gain the student’s attention

During the direction:

- Use a calm, neutral tone of voice

- Incorporate choice when possible

- Keep requests clear and concise

- Consider using declarative language for particular students who struggle with concrete demands

- Avoid ultimatums, reminders of punitive consequences, and authoritative language

After the direction:

- Give space

- Provide time for the student to respond

- If the student appropriately engages, provide positive feedback (if student responds well to this)

- If the student does not respond consider why might that be:

- Stay calm and regulate yourself before responding

- Consider what might be going on for the student that is making it difficult to cooperate

- If approachable, see if they are willing to share what it is that is bothering them and go from there

Like we said, it’s just being nice when we get to the core of it all. A more therapeutic-type approach is beneficial to ALL students, not just ones who dig their heels.